ANNOUNCEMENT: The second week of June I will be traveling to Francavilla for a week of digging into the archives and walking around town to identify buildings of relevance for these essays. I do promise a report upon my return. So…the July essay may or may not be delayed somewhat. I will also spend some time on the road here in the U.S. when I get back. If you want to come along in spirit, here is my playlist for the road: Pop’s Highway Tunes on Spotify. Not to be confused with a list by the same name that existed previously on Spotify, but unknown to me. They intersect in surprising ways (Johnny Cash’s, A Boy Named Sue for one).

Back to business:

This month’s essay aims to give a general feel for the kingdom of Naples and Francavilla at the beginning of the 1600s. It is meant as a context for the continued narration of the lives of Argentina family members as we move through the generations. Due to its wide angle focus it is presented with broad brush strokes and lacks depth, but I believe it is a useful introduction to this time and place. A list of works will be listed at the end for those wishing to explore this period further.

Donna Laura would continue to live more than twenty years past her nephew Josephi, would see the birth of his first son Giovandonato in 1578, would still be around for the birth of Giovandonato’s son, Pompeo, in 1608, and when she died in1615 it would be in a different world than the one she was born in. When she began her life, the tumultuous decades of the Italian Wars had come to an end and the Spanish crown was beginning its rule of the kingdom of Naples, but by the end of her earthly journey, the Spanish control was showing signs of stress even as its dominance in the kingdom of Naples was reshaping the region’s culture. This did not leave her town of Francavilla Fontana unaffected, and through Laura’s life, under the benevolent ownership of the Imperiali family, the town was in full expansion and in its institutions there began to appear glimpses of the modern world.

What was going on with Spain? The Iberian Empire was overextended and maintaining its far flung colonies was costing more than it could afford and the supplies of silver taken from the Americas were drying up by the 1620s. In 1596, the crown’s debts had been consolidated into a single, interest laden debt, but since that arrangement, budgets kept running in deficit year after year and the Crown was able to keep going only on the expectations of future yearly bank loans, secured on the faith and credit of the largest Western Empire of the time. That was the situation before the Thirty Year War began to sap the energies and resources of the Spanish Crown even further.

The economy on the Italian peninsula had been going through a decline beginning during the last couple of decades of the 1500s, and in 1585, a grain shortage caused hunger riots in Naples, requiring the viceroys and the king to expand energies in a place that had not caused them much worry so far, evidenced by the fact that Spain never garrisoned more than 5,000 soldiers in the entire kingdom of Naples during the centuries it controlled it; most of them around the capital city that by the year 1600 was the largest in Italy with half a million citizens, and equal in size to Paris and London. Mediterranean countries had ceased to be a source for grain exports, Baltic states taking the lead in that commerce. Also, unresolved issues with the Ottoman empire and improved navigation made the Mediterranean less relevant as ships began to traverse large oceans and the maritime countries in Northern Europe looked outward for their commercial enterprises. Due to the pecuniary difficulties and the inability to pay a large standing army in the kingdom made it necessary for the viceroys in Naples, entrusted with the crown’s business, to walk a tightrope in their relationships with the nobility, the clergy, the professional class, and the masses. Whenever possible they let the barons and landowners run the faraway cities and lands they owned as if they were independent mini states in which the latter had all civic, judicial, and economic powers. A nominal nod to the Crown in Naples and the payment of taxes extracted from the population was all that was required for the quasi-nobility to keep avoid undue attention from Naples. Whenever the rural barons became too extractive of the population’s labor and were excessively cruel in their dealings, the crown did what it could to appear on the side of the common citizen to avoid a popular revolt and maintain the status quo. As written in statutes, the law and the Crown were the ultimate rulers, but for those who toiled in small rural towns, Naples and the courts were very far away. The nobility flexed their power and autonomy and gained some concessions from the Spanish viceroys who had few tools against it: they gained the ability to retain their hereditary titles in the family, and even if there was no child born of a noble, the title would pass to the next in line through the offspring of siblings, whereas in the past, the title had returned to the crown. Since the noble class, as well as the clergy, was exempt from direct taxation, there was a high demand for those titles, a demand that the viceroys satisfied by creating and selling them to raise funds for the royal coffers. Whereas in 1590 there were 118 noble titles, by 1613 there were 161, they grew to 271 in 1631, and 341 in 1640. Some of these titles were gained by purchasing a piece of baronial land that had a title attached to it. Nobility was no longer appointed by the monarch with the expectation in return of loyalty, soldiery, and funds when requested as was the feudal custom of old, but rather it became a classification that allowed for advantages in taxation, and social standing. It also became a commodity that could be purchased or married into.

In lieu of the expense of an armed occupation, the Spanish found common goals with the Catholic Church, newly energized after the Council of Trent and working vigorously on its Counter Reformation efforts.[1] In consequence, there began in the kingdom, a homogenization of belief and religious dogma, a congruence of State and Church, and efforts to eradicate pagan and non-Catholic beliefs amongst the population, that morphed Terra d’Otranto from what had been a multicultural region to a place of diminished cultural diversity, a place that after the expulsion of its Jewish population in 1540, also saw the elimination of Greek rites in most parishes by 1620. The Crown of Spain aligned itself to the Church to legitimize its presence with the understanding that being in opposition with one would mean to be in opposition to both. The State participated more actively in religious rites like processions for a city’s saint’s day, Easter, and other major events in a city’s civic and religious life. The Church and the State also increased the number of institutes for the aid of destitute families and individuals, a move intended to keep the vulnerable population from taking arms against those governing them, and offering in consolation for lives that could be short and brutal for the poor, the promise of the eternal rewards that were waiting, and that their earthly tribulations were but temporary. The Church became an essential partner with the crown in keeping Spain in control of the kingdom. The numbers in the clergy increased during this period, and in cities like Lecce, in the heart of Salento, they reached 10% of the population. The Spanish Catholic leadership found this increased presence necessary after inspecting remote villages in the south and reporting that they had found “…the Indies down there…”. In other words, the pagan beliefs in rural towns of the kingdom of Naples were no better in the eyes of Catholic missionaries than the indigenous practices found in the New World. New religious orders were approved during this period and many came to the southern part of the kingdom, like Terra d’Otranto, to help enforce proper Catholic belief and behavior in these ‘pagan’ communities. As the religious orders established themselves, they were also filled by clergy from the local population who often retained local customs, thus blending Christianity and paganism according to each town’s individual flavor. The clergy in many towns remained strictly local, as the property of the parish, which could be as extensive as that of a major landowner, was collectively owned and managed by its abbot and priests. Though the practice may have brought stability to the Church, it also instituted a parochialism that became insular and not receptive to exchanges of ideas that might be flowing around elsewhere in the Italian peninsula or the rest of Europe. Partly as a consequence of this parochialism, combined with the decreased naval traffic and commerce from Terra d’Otranto caused by the decline of trade routes in the Mediterranean, there begins a relative isolation of the region for quite some time. Though this shielded those who lived there from the tumultuous events that would engulf northern Italy and Europe for much of the 1600s, it also isolated the region from an examination of social and cultural trends happening elsewhere.

Many in the religious class had been members of noble or wealthy classes and had received a solid education, but in contrast, the large majority were not educated and merely learned the required passages in Latin, and often not even correctly, and they would interpret for the citizenry the meaning of Scripture to the best of their abilities. As opposed to the Protestant belief of a personal relationship with the Divine through the reading of Scripture, Catholics were made to depend on the intercession of the clergy for their relationship with God, since most could not even understand the Latin in which the masses were performed. Notwithstanding this heavier presence, the Church in the communities of the kingdom did not eradicate superstitions, beliefs in miracles, and the possibility of petitioning saints and dead ancestors for successful earthly outcomes. The veil between the dead and the living remained thin and a mutual relationship of dependence existed between the two worlds. The dead needed the living to perform masses for the benefit of their souls, and in exchange they sought advice from the dead in conducting quotidian affairs or predict future outcomes. Among the many documents in the family archive are final wills which include payments for future masses according to the financial ability of the newly deceased. Though Spanish Catholicism became the energy that secured the stability of the kingdom for the Spanish monarchs, in many cases it was a hybrid form that absorbed pre-existing beliefs.

There were limits to what the Church would tolerate and this century saw a trend towards anti-intellectualism from State and Church. Even as a passion for the re-emergence of long lost Latin and Greek texts was viral amongst the learned and the artists, the viceroys in Naples were closing down universities and centers for study that had previously attracted scholars from all over Europe. Ideas that were circulating elsewhere in protestant Europe were not welcome in the Catholic world. If one were to propose, like Giordano Bruno for example, that it might be worth considering the atomistic ideas presented by the newly re-emerged ‘De Rerum Natura’ written by Lucretius in the 1st century BCE, such proposal would lead that person to the burning pyre, as it did to Bruno in 1600. Francavilla’s own were not immune, as Marquis Giovan Bernardino Bonifacio the last Bonifacio ruler of the town, was forced to leave town due to his alleged interest in Lutheran beliefs. He became a roving scholar and ended up first in Florence, where he published a translation of ‘De Rerum Natura’ and finally ended up in faraway Danzig where after establishing a library, his life ended in the first decade of the 1600s.

What was Francavilla like during this time? In 1595 there were 994 hearths, but that is very likely an undercount.[2] Following the permission granted by Giovanna IV in 1517, the city started filling in within and expanding out of the original city walls. Often this happened by the emergence of small aggregations that would, in time, be absorbed into the larger city. One of those centers was around the original old chapel from 1310, which had now been expanded a couple of times, and reopened in 1572. Placed in what is now via San Giovanni and a short distance from the Imperiali castle is the area where one of a few Argentina homes of the period were situated. A balcony from one of those homes still exists, and though it is now attached to a newer building, it is still within the same area.

One thing that I have not quite clearly figured out yet is why it is that up to this period most Argentinas were born in nearby Oria but already owned homes in Francavilla. It is possible that Oria, where the family originally settled, is where the families of many of the wives lived, and that is where the births happened, since all births happened at home.

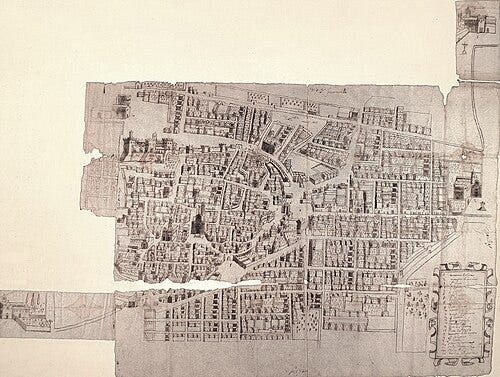

The structure of Francavilla started taking its shape at this time with streets that radiated from the castle and led toward the main churches and the subdivisions built around them.

Street map of Francavilla Fontana from 1643

Buildings were becoming more permanent and built with local stone, which often was the soft and easy to cut ‘tufo’. The homes of wealthier citizens had more than one level, and their families lived in the safety of the upper level while the street level floor was organized for the housing of horses, and storage of carriages, tools, and provisions. Some of the bigger houses also had subterranean cellars for the long storage of oil and grain. In many cases, these cellars were walled in and forgotten through the centuries but on occasion rediscovered during the rehabbing and modernization of these old buildings and turned into great wine cellars. Parts of the buildings at the street level were sometimes rented out to artisans and craftsmen who plied their trade in the front and lived in small rooms in the back. Interior courtyards designed for light, a safe outdoor environment, and growing fruits and vegetables were common in the bigger homes. Historian Pietro Palumbo lists in his book about Francavilla some of the families that arrived in the area from locations far and near, attracted to the economic possibilities in Francavilla and relative stability of the region. The Argentinas are mentioned, as well as other families whose names I noticed in documents in the archive. Palumbo explains that many families with means moved into the area, none of them noble, but many ‘behaving as they were noble’, having achieved wealth as part of the new professional and landowning class. Many achieved noble status through marriage or purchase of land with a title attached to it, as would happen to the Argentinas in a short while, becoming a data point in the trend of the inflation of titles of nobility under the Spanish rule. Palumbo also notes that the Argentinas had arrived in the area by way of France, underscoring the notion of the first Argentina in Italy, Robertus, being part of the army of Charles of Anjou who came down to Naples in 1266. Among the new arrivals there were many men of arms, of which the Argentinas produced few, many who entered the clergy, to which the family contributed larger numbers, those who came to buy land, and also those in the legal professions attracted by the opportunity for lucrative careers.

Just as elsewhere in the kingdom, Francavilla also experienced an influx of religious orders. Carmelites settled in town, and attracted Filippo Argentina, who after a short marriage and career in law, became a distinguished theologian in that order. The Basilian order was there and Capuchin monks arrived, known as ‘Frati Minori Osservanti’, a branch of the Franciscans. Also, the Oratorian Fathers were present and founded the first public school for poor children in Francavilla in the late 1500s. The Imperiali family also was a positive force for the support of those who needed help in Francavilla. They presented a proposal to viceroy Pedro de Toledo in Naples to open the first institution that would provide material aid but also moral guidance for the poor, the indigent, and the very young. Fully supported by the Imperiali, it loaned money at no interest for those who demonstrated a need. The institution was approved and would operate until Napoleonic times.

These examples of beneficence demonstrate a city that had the will and means to maintain institutions that helped those in need, but it cannot be ignored that these enterprises of social assistance do not signify any desire by the elites for social change. This was a society with well defined castes, and there was no expectation that the situation would change. The wealthy helped secure a safety net for the poorest for reasons of Christian charity, but as well to avoid civil unrest and to secure a labor force when harvests were needed. Those who toiled on farms and cities needed the wealthy landowners for the wages they offered. It was a relationship that lasted through generations and rarely would the arrangement be disturbed by social upheaval.

Having set a general context for the beginning of the 17th century in Francavilla, the next essay will focus back on the Argentina family, and its primary protagonists during this period.

[1] By the beginnings of the 1600s European governments shared the understanding as Geoffrey Parker writes, “…the faith of the subjects should be the same as the fate of the rulers”.

At this point of the project, these essays are not being presented as academic essays with full annotations and citations, but more like initial research notes. At the end of each essay, I include a list of consulted works for the reader to explore. After this initial phase is finished, the entire work will be edited and proper citations will be included. Thanks for being part of this initial exploration.

[2] A hearth (a fuego) signified a family unit and was also a unit of taxation for the family and the owner of the city.

WORKS CONSULTED

Astarita, Tommaso. Between Salt Water and Holy Water: A History of Southern Italy. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2005.

Croce, Benedetto. The History of the Kingdom of Naples. Translation of Italian 1925 6th edition by Frenaye, Frances. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970.

Dauverde, Celine. Church and State in Spanish Italy: Rituals and Legitimacy in the Kingdom of Naples. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Palumbo, Pietro. Storia di Francavilla Fontana. Reprinted 1974, Arnaldo Forni editore. Noci (BA), Italy: Editore E. Cressati, 1901.

Parker, Geoffrey. Europe in Crisis: 1598-1648. 1st ed. History of Europe. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1979.