10. DESPERATELY SEEKING LAURA

1. A description of the documents that fueled the story. 2. An historical fiction based on real people and the documents they left behind.

This month’s essay is a bit long. But it’s in two separate parts and you can decide how to go about it. I believe they belong together.

Laura Argentina who died in 1615 is now not much more than a document. She’s a piece of old paper among hundreds of others in the collection of family documents that go back to 1466. She is document number 5 in folder ‘One’ of a couple dozen folders each containing an average of 250-300 documents, many of which are multipage. She is nestled between number 4, a private correspondence by her nephew Josephi, from her older brother dated 1590, and number 6, a document that certifies that in 1794, a Ferdinando Argentina paid some other person to assume his military service and kept the paperwork about it. Yes, the thousands of documents are not in chronological order, that’s the fun part. What remains of Laura is in that single page in that first folder; she is very close to permanent oblivion, but I’m interested, I want her to be around just a little bit longer.

Ancient Laura Argentina died on the same date, March 29, that the latest Laura Argentina, a dear niece, would be born three hundred ninety one years later, a fact that was not noticed until a few years back. I looked at the family tree and at the distance in time and in place between them and wanted to learn more about the old Laura, one of our ancient mothers. Not just because she shared a name and a date with my niece, but also because there just aren’t that many references to women in the early centuries of the archive. In the androcentric organization of the family records, women just appeared as daughters and wives and most of the data did not concern itself with much more than birth, marriage, childbirth, and death dates. But here was a document in which a woman was the center. What could I learn about an ancestor who lived over four centuries before I was born, left little trace of herself, but whose DNA is also part of mine?

What follows is two separate essays: the first describes what I could find out from just a single document. Then, having run as far as I could in researching Laura, but still wanting to create a life for her, I indulged into a plausible – love that word – history for her. I created an historical fiction story based on what I learned from the documents, what I know from the context of the family, and what I have learned from scholarship about the area at this time.

THIS IS THE BACKGROUND.

Sometimes in the mid-1970s my dad’s brother, Feliciano, accomplished the herculean effort of organizing the thousands of documents that the family had kept scattered and unlabeled in boxes since the 16th century, of organizing them in folders. I don’t understand his method as the folders and the documents within are not organized in chronological order, but at least each folder has an index of the documents with a one line description and the relevant date. Maybe that was a first phase and he catalogued as he was going along, and then would organize them at some point later, and for that I am ever so grateful to zio Feliciano and wish I would have told him so while he was alive, but I just had no idea what he was doing. He was such a mysterious man to me, working quietly in his strange study, full of old swords on the walls, uniforms, guns, medals, stuffed exotic animals, and books…books, many of which he was the author. Anyway…the description for document number five, translated by me from the original Italian of zio Feliciano, is as follows: “Renunciation of hereditary share of Laura Argentina who married the nobleman Giuseppe de Adam in 1568 for the benefit of Gaspare”.[1] Gaspare was her older, but not the eldest, brother, who also happened to be an abbot for a religious order in Francavilla, possibly Carmelite. Upon reading the description, what came to my mind was, “What the hell was that all about?” In a description in his book about the family, Feliciano states that this happened with “…consent of her husband”. So that’s the quest. Why did Laura give up her rightful third of an inheritance that earned the monicker ‘noble’ before her name, an inheritance that was not unsubstantial? (The customs of the Kingdom of Naples as opposed to the primogeniture winner take all practice in much of Europe, split inheritances among all siblings). And why was Laura’s husband ‘consenting’ to his wife’s, and basically his after marriage, share of the inheritance being legally and without recourse turned over to her abbot brother Gaspare?

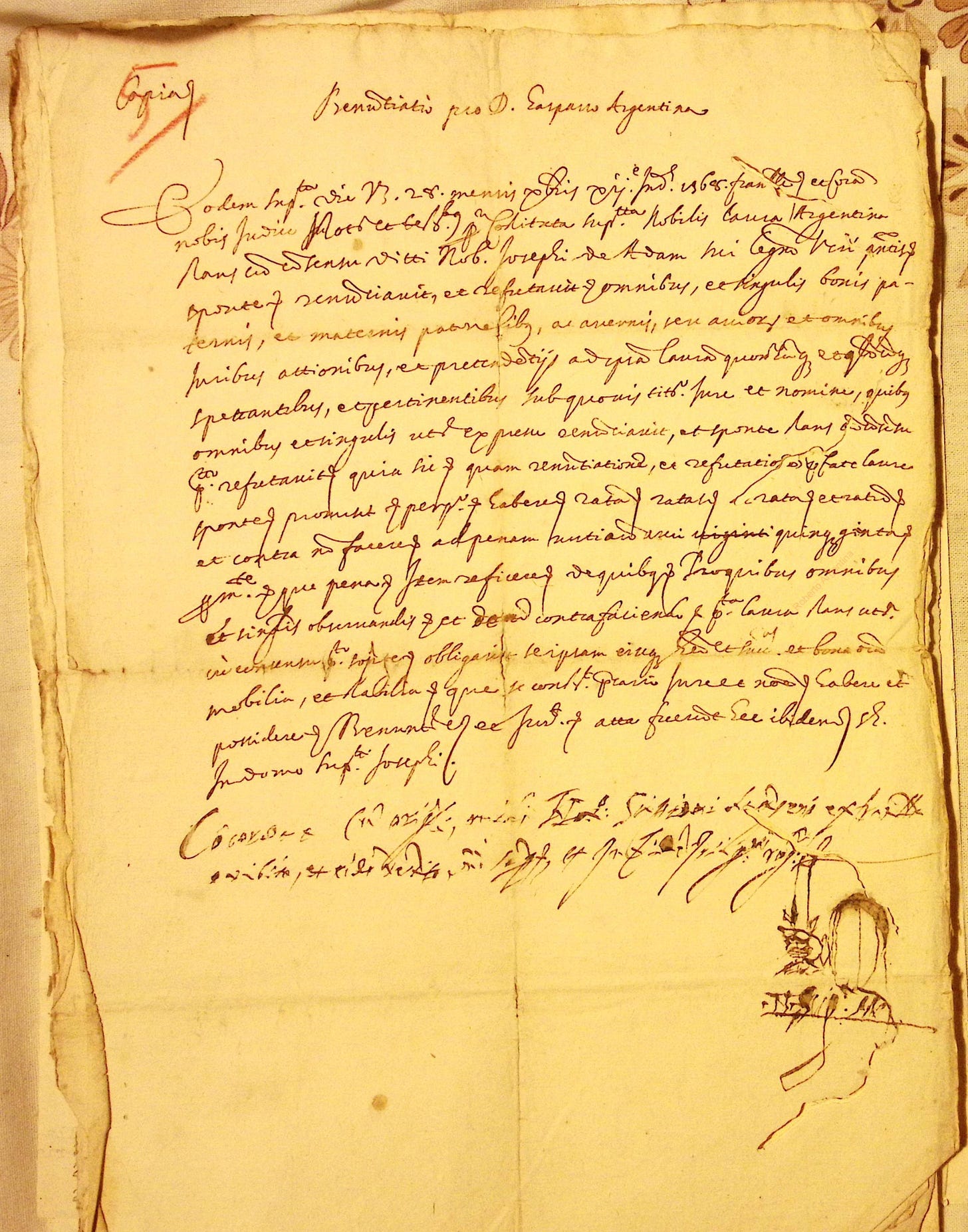

I fully recognized there would be limitations to what I might be able to ultimately learn, as all I had to go on was document number five of folder number one. And that document was written in late stage Latin, also using legal terminology that was used in Francavilla at the time, and - I found out later - abbreviations thrown in the text. At this point, dear reader, I must confess that this is not an area of expertise of mine. My certification for reading handwritten documents from southern Italy in the 1500s, is ‘enthusiastic amateur’. It was an amazing experience to look at, touch, and delicately handle a document that had been looked, touched, and handled by the elder Laura Argentina four centuries earlier. Once that emotion wore off, I scanned it among hundreds of other documents and put it back. But more so than with other documents, it never really left me, and at some point I became determined to find out if it could reveal something more about Laura. (Pronounced Lah-oo-rah, by the way; stop reading it with the English pronunciation of Loh-rah … go on… just practice it before you keep on reading).

I thought through all the constraints I faced in learning more about Laura from the document. A document that, though short, is written in cursive without, what appears to me anyway, excessive care for a clear calligraphy, as opposed to other documents in the folder that are beautiful to behold and written with an elegant hand. On the top left of the document the word ‘copia’ is written. The document is a copy. I wondered if it is a copy written later because the original document was decaying, but I don’t think so because the paper seems similar to other documents from the same years, and also because the very intricate symbology that was part of the notary’s signature is present in this ‘copia’. Again, I am not expert in this field, but I believe that the word copia is there because it is one of three or more documents produced for the contract, each written by hand by the notary or a scribe assigned to the task. There would be a need for at least three copies, one for Gaspare, one for Laura, and one to be submitted to the administrative jurisdiction in the city. My guess, and it is just that, is that the writing of this copy was maybe the second or third execution of the document, and the reason for the poor calligraphy is that writer just wanted to get it over with. Or maybe readers of the time would not have found this handwriting so illegible, though there is evidence of other documents written with much better care. Regardless, it is a slow and difficult task to transcribe the words, and I have done so very slowly, one by one, by zooming in to each letter sometime, and even then, I have succeeded in identifying only about half of the words.

Document # 5

With this result I have first tried to cobble a meaning from what I had and also fed my partial transcription in an A.I. application I am training for this purpose and asked it to create a probable meaning from the partial text. This path gave me a couple of slightly different interpretations. I also fed a pdf of the entire document into the A.I. tool and had it give it a spin. It read some words accurately, some not so much, and others it could not read at all, but it analyzed what it had and came up with a transcription, a translation, and a possible summary and meaning of the document. The analyses are interesting, I ran more than one, and seem very plausible, but, and here is the problem with using A.I. tools: I realized that it was giving me an analysis of what it thought it read correctly more than an actual transcription, an analysis on what the document might be about based on whatever context it has access to, and so creating a probable result, but not based on an exact transcription and translation, but rather by creating a likely meaning based on the partial text and similar types of documents it has access to. An important difference, and as much as it is enticing to accept the conclusions the A.I. tool produced, it is necessary to understand that they might not have been created based on the actual text, but only intuited based on a transcription, at parts incorrect, of the text. When I ckecked word for word, I realized that my transcription was more accurate. When I questioned the bot about its obvious transcription mistakes it replied that, yes indeed, the words were not transcribed correctly, but it acted so to prepare a cohesive understanding of the document as a whole. More about that later.

The next constraint I face in understanding the meaning of the document, even if I finally translate it word by word, is placing it into a correct context of the times and making sense of the legal words and concepts as they relate to mid-sixteenth century southern Italy. In this I can find help, as I know people in the legal profession near Francavilla who also are scholars of local history and can help me make sense of the document. But, getting back to Laura, why does this document even exist? Why did she do it? Why did her and her husband do it? Why did they give away her inheritance upon marriage or soon after, and why to her older, but not eldest, brother Gaspare, who was an abbot in a religious institution?

A quick reference of the principals so far.

What do I know about Laura? She was the third born and only daughter of Giovanbattista Argentina, who bought an olive grove outside of Oria in 1526, in addition to other property inherited from his father, Roberto, who made an earlier purchase of land in 1480. Laura’s eldest brother was named Roberto, named after his grandfather, and the second born, Gaspare, possibly named after a grandfather from the maternal side. We have two dates for Laura’s life: 1615, when it ended, and 1568, which is the year of the document, and also the date that Feliciano lists as the year of her wedding to Joseph d’Adam. I don’t how Feliciano established 1568 as the marriage year because there is no other reference to it, but he may have gotten it from church records[2]. If we presume that Laura married at the age of twenty to twenty-five, it would put her birth to around 1545, which would make her about seventy at the time of death. This is not insignificant because it means that Laura lived decades longer than a woman’s average expected life span in Terra d’Otranto in the middle of the 16th century.[3] This can be explained not just by genetic advantages, but also by the fact that at this point, about a century after the original Giovambattista’s arrival in the region, the Argentina family was becoming a family of landowners whose members did not spend laborious years working the land, but were enjoying the privileges of economic success, or at least, were removed from the hard labors of the agricultural workers. In the second line of the document, when her name is introduced, Laura is preceded by the title of ‘nobili’, which may be a signifier of the Argentina family’s status, or possibly it was attached to her upon marriage with Joseph d’Adam, who did come from a well established professional family from Oria, where the Argentinas still lived until the middle of the century. In Pietro Palumbo’s book[4], a frequent source for early Francavilla Fontana history, the Argentinas are in the latter part of the 1500s already described as ‘Signori’, a more modest classification than what we think of an English Lord, but still within one of the top families in Francavilla already. Be that as it may, she lived much longer than typical for a woman of that period. I have found no records of children, and possibly there were none, which would have had a beneficial effect on Laura’s longevity as childbirth was a leading cause of death for women in those days and long afterward. But let’s get back to document number 5 and what it may reveal about what happened to Laura’s inheritance.[5]

The first possible interpretation is derived from my own Latin transcription of the document using only about half of the words in the document. As hard as I tried, I could not make out the rest. The document begins with the words: ‘Prenuntiatio pro Don Gaspare Argentina’, an announcement, or declaration found in legal documents of the time, in favor of Gaspare. The date shows the year of 1568. When I fed my transcription into the AI model to see how it would be interpreted, I also provided some background context about Laura’s husband and brother. By the way, I know there are those who will have serious objections to this process of using AI tools and their limitations in this task, some of which I already mentioned. I respect that. Due to my own limitations in being able to read the older documents, I am using any tool at my disposal while being fully aware of the potential inaccuracies of the results. As far as the usefulness and ethics of using AI tools for this kind of work are concerned, that discussion is for another day, for now I am just mentioning its use in respect of full transparency. I used a couple of AI platforms, and while one AI tool was confident about its work, right away I could see that there were mistakes in the transcription and what the words actually were, even some names were wrong. The second tool prefaced with the conditional statement that it was a hard document to read, and did I want it to try anyway? I answered affirmatively just to get a sense of the current competence of these tools in reading old cursive writing. The first transcription tool gave a result for each word, but many were very much off the mark, the second one was more honest and showed were […] it could not identify words instead of trying to come up with a result. I settled on one AI application and asked it to both read the scanned document but also take into account my initial transcription work. The AI tool I used, which I have decided to name HAL, must have intuited that I am partial to flattery and complimented me on my work so far. Wanting to appear demanding with my new assistant, I began questioning its reading of every line and sometimes word. I realized there was much, and please excuse my vulgarity, excrementum tauri to some of the transcription. I could see it working to make sense of it, and I learned quite a bit from my questioning of HAL’s work. It was so hard to transcribe this document because the scribe wrote words like ‘legmo’ which I could not make heads or tails of it, until HAL suggested that it might be a shortening of ‘legitimo’, which made sense in the sentence.[6] For the word ‘Godem’, the very first word in the first line, I was also given an illuminating answer.[7] Is the answer provided correct? I don’t know, but it is tempting to go with whatever HAL puts out with authoritative certainty. I also realized going over the transcription that the software does not really try to read word by word but rather try to gleam a meaning from a few words. I had to question HAL over and over about why some words in the transcription were not visible in the actual text, and the replies had very intelligent sounding excrementum tauri. My limitation with a complete and accurate translation of this document is not being a specialist of this period and not having enough time to really dig into it to achieve that result. Be that as it may, here are the main takeaways that are constant from the different approaches I tried:

· It’s a formal renunciation by Laura of her hereditary rights in favor of Gaspare.

· It’s an official document prepared by a notary, and Laura recognizes that she is ceding her property without possibility for a future legal recourse.

· The document mentions both maternal property, paternal property, and movable property as well as real estate.

· It has precise legal terms with relevant obligations and penalties in case of breach.

· Her husband, Josephi de Adam, was possibly not there according to different interpretations of the document.

Any readers out there who want to help out, please feel free to have a go at the document, and let me know what you figure out.

A SHORT STORY ABOUT LAURA ARGENTINA

This is a rough draft and needs work, but I wanted to get it out anyway.

The chapel’s old walls were coated with the soot of candles and prayers, residue of decades of light and hopes nightly burning themselves out. Donna Laura rubbed the dried skin of her old hands while fumbling the rosary through her bony fingers. In the light of a single olive oil lantern, in the small chapel of the house she inhabited most of her life, she silently nodded and soundlessly mouthed the responses to the evening prayers her older brother was reading. Was she even aware? She knew the responses by rote after thousands of repetitions, and so her mind was free to wonder while staring with half closed eyes at a picture of Mary and her Child. After all those years, she still ached for her offspring to be there with her in that house, but none had ever been born. What was the point then of enduring such a long life, after a long marriage, and having no one of her own to see her to her grave?

Years of hope had turned into years of anger, which led to years of defiance, which finally were followed by years of acceptance. Her life’s work then, became the advancement of the family, a skill she was naturally suited for, and passing on what should have been her offspring’s properties to her nephew Giuseppe, as he was named by her eldest brother Roberto, but called Josephi, as she made sure, in honor of her late husband. Her husband was Joseph d’Adam, who she loved at first sight, then later hated, and with time learned to appreciate and coexist with, and not without pleasant times. She had always been close to her older brother Gaspare, the abbot, who she made her reluctant functionary in establishing the Argentinas as one of Francavilla’s leading families within her lifetime. Neither of them with a son nor a daughter, they dedicated themselves to Josephi. Laura had to work on Gaspare, who would have preferred nothing more than to be left alone in the solitude of his books and silent walks in the country, but was essential to her desire to increase the family’s properties. She was not willing to let what had been acquired over a century become fractured away into irrelevance. Her father, Giovanbattista, had grown the family’s lands with the purchase of a productive olive grove in 1526, building on what her grandfather Roberto had started with the 1480 purchase of a tract between Francavilla and Oria. Roberto had been able to purchase that first piece of land with money left to him by his father Giovambattista who had moved to nearby Brindisi and then settled in Oria in the mid-1400s after a military life that began in Naples with the Aragon army. Donna Laura never met either her grandfather nor her great-grandfather, but their stories inspired awe, and respect, and gratitude, and expectation, obligation even to continue on the same path. The instructions from her ancestors’ ghosts were clear: land. More. As opposed to her older brothers, Donna Laura knew land and how it was worked and how it was made to profit. She learned from her father, Giovanbattista, who always took her with him when he went to the properties where she listened intently while he directed the field hands who were working them. Always nearby when they talked about weather, harvests, expected prices for the commodities, about the health of the animals, and often just mundane conversations between the man who owned the land and those who worked on it. Out of the three children she, the youngest, was the only one with a passion for it, the only one who understood. Her father had taught her how to be practical and realistic, and generally she had more common sense than her two brothers put together, and her husband as well, to tell the truth. Roberto, her eldest brother, had been cowed into anxiety by his father his entire life and avoided risk as much as possible and Gaspare entered the religious life to escape that same pressure. Only Laura stood the test, won the respect of Giovanbattista, and learned to take to heart his hard lessons.

She did not have a propitious start in following her father’s footsteps. In 1568 Donna Laura was forced to sell off her share of the inheritance passed on to her, a share equal to that of her brothers. She handled it alone in the notary’s office. She scorned how the scribe finished writing the document in a much too careless and impatient manner – she noticed that it was hard to make out some of the words – regardless, from that moment, a moment she shared with no one because her husband was not even present there for the signing, from that moment she became silent with anger for months. Soon after marrying she had found out that her new husband, who came from a prominent, noble, professional family, was heavily indebted and needed her inheritance to pay off his debts. It’s not that he didn’t love her, he did, but he also needed her money. For Donna Laura that was the beginning of the hating period. Once home, she left the document in plain view for a long time, and Joseph did not have the wherewithal to remove it, and there it stayed until it collected too much dust, and Donna Laura finally stored it away in a folder with some other papers. She had convinced Gaspare the abbot to use his funds to buy her inheritance, funds that she used to release her husband from his debts – their debts. The couple remained in the house that they had sold to Gaspare and kept the furniture that they had sold to Gaspare; it was all his property, but he lived in the convent, and so they stayed, waiting for a child that would never come.

Once Donna Laura came to terms with certain realities about her succession, after spending a few morose years making vows to this saint and that one, paying tributes from one holy image to the next, funding charities her brother Gaspare promoted, realizing finally in disappointment that Gaspare had no pull with any Heavenly operatives, she began to change her mission and dedicated herself to acquiring properties for the posterity of the Argentina family. That is how she would honor her father, the only man who took the time to really know her. The decade between 1575 and 1585 were the years of opportunity: guiding a reluctant Gaspare, Donna Laura sued, bought, and gathered a fair amount of profitable land for the family. After she died numerous documents were found that recorded all these transactions that Gaspare conducted on her behalf. Most of them did not make it to our days, but what remains is an indication of the activities of those years. There is the 1575 petition to the Camera della Summaria, the final administrative arbiter for all commercial matters in the kingdom, all the way in Naples, for land on which she argued they were owed ‘decime’, or portions of the profits. There also remains a contract from later that same year for the purchase of an additional parcel of the Lama delli Gatti property, adjacent to the one her father Giovanbattista had originally purchased in 1526, and a property he had always wanted. Laura, who had walked those lands her entire life, felt satisfaction in continuing her father’s quest, something her brothers could not possibly understand. When her nephew Josephy managed to buy the final parcel of Lama delli Gatti, as attested by a ‘quietanza’ dated 1590 in Josephy’s papers, Giovanbattista’s quest was retired.

Donna Laura managed to protect what she gained. Another document that survived to this day is the certification of all the family properties designated as feudal properties, and passed on to her nephew Josephi in 1585. Through Gaspare and his untaxed connection to the Church, the profits were kept away from the Crown’s longing arms, all for the benefit of Josephi, for the benefit of his future family, that was what she worked tirelessly for. Managing the properties as her father had taught her to do, selling the harvests to the best advantage, taking care of the field workers without giving up too much, finding the loopholes to remain untaxed. Things that her brothers cared little for or even had any instinct or aptitude for.

Giuseppe, named Josephi, the eldest son of Donna Laura’s eldest brother Roberto and his wife Alfonsina Cistone had been born sometimes around 1550 or soon after, and had by this decade of frenzied contractual activity achieved what Donna Laura never did, a progeny. He married Caterina Palmerio from Oria, and their firstborn, Giovandonato, who would carry the family name, was born in 1578. From him would issue Pompeo in 1608, who would become in due time, the first Argentina mayor of Francavilla.

Donna Laura, praying in her chapel, reflected on the fact that she lived to know her father, Giovanbattista, lived passed her elder brother Roberto, lived through to see her nephew Josephi, for whom she worked as if he was her own, saw him die in 1594, at the age of forty-five or so, saw through to the birth of her great-nephew Giovandonato in 1578, and lived improbably to witness the birth of Pompeo, her great-grand nephew in 1608. ‘It’s too much…’ she thought sitting in her chair in the chapel mouthing her prayers and rubbing her rosary. She glanced at Gaspare through nearly closed eyelids and without voicing a sound: ‘Why has God forsaken me? What more does He want from me? Haven’t I done enough? When will I be released?’ Donna Laura was released to her God in 1615, having lived through four generations and having single handedly secured the future for the family in Francavilla.

[1] Argentina, Feliciano. Gli Argentina Nel Salento. Galatina, LE, Italy: Congedo, 1978.

[2] After the recent Council of Trent, parishes were required to record important religious dates for their parishioners. Those often were baptisms, first communions, marriages, and deaths.

[3] Safran, Linda. The Medieval Salento. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014.

[4] Palumbo, Pietro. Storia di Francavilla Fontana. Reprinted 1974, Arnaldo Forni editore. Noci (BA), Italy: Editore E. Cressati, 1901.

[5] Feels odd naming her Laura because if somehow I were to meet her she definitely would be at least ‘zia Laura’ of ‘Donna Laura’, and I would show proper obsequiousness to an elder in the family, regardless of my own age.

[6] Third word from the right, third line down not counting title line.

[7] HAL says: “In early modern Latin documents, especially from southern Italy and Spain, notaries often began with formulas like:

· Hodierno die... (On this day...)

· Die hodierna... (On the current day...)

These were sometimes abbreviated, adapted, or distorted over time due to scribal habits. “Godem” may be a contracted or phonetic spelling of hodie or hodierno die.”